Because it’s a full-contact sport in which objects are wielded with high velocities near players’ heads, lacrosse was an apt choice for researchers to study.

Using accelerometers attached behind players’ ears, researchers can measure impact in real time, letting them pinpoint the exact hit that caused a concussion. They then review the circumstances and severity of the hit.

The accelerometers are set to trigger with an impact of 10 G, which excludes basic activities like running or jumping, Mihalik said. The average football impact is around 22 G, while concussion impacts often exceed 80 to 90 G and have been measured as high as 168 G — more than some high-speed NASCAR crashes.

But suffering a hit over 80 G doesn’t necessarily cause a concussion for an athlete, he said. There are a multitude of factors that contribute to whether an athlete sustains a concussion or not, though researchers don’t yet have specific answers.

“Why can someone get involved in this 35-mile-per-hour car crash on the field and pop up and be perfectly fine and someone else not?” Mihalik said. “That’s what we’ve been trying to figure out for the better part of a decade now.”

Lacrosse is one of the fastest growing sports in the U.S., due in part to the popular perception that while it’s still a contact sport, collisions occur much less frequently than in football.

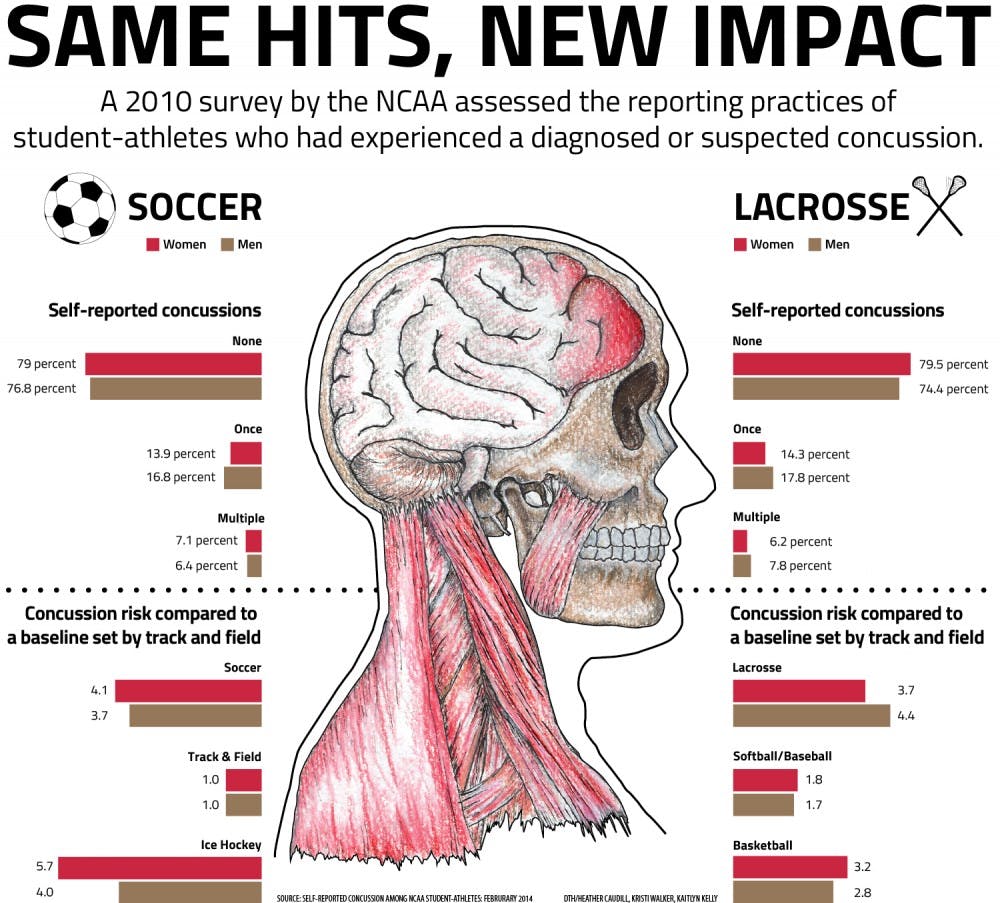

Although the body of research concerning concussions in lacrosse is still in its infancy, it does show that lacrosse yields the third highest concussion rate for youth sports behind football and hockey. A study published in 2014 by The American Journal of Sports Medicine found 22 percent of injuries suffered by high school lacrosse players between 2008 and 2012 were concussions.

“Unfortunately, it’s relatively common in our sport,” North Carolina men’s lacrosse coach Joe Breschi said. “We’ve lost probably five kids for their career from multiple concussions.”

Player-to-player contact is the most common cause of concussions in the sport. Players can be blindsided by hits, and the hitting players can give themselves concussions by leading with their helmets. To combat this, coaches and referees emphasize ‘heads up’ hitting.

“If you’re taught the proper techniques, it’s pretty hard to get a concussion,” said Patrick McCormick, a freshman on UNC’s lacrosse team.

Possible rule changes in the men’s game include face-offs, where two players are crouching and have to fight for possession of the ball, and increasing the penalty referees give for ‘headhunting.’ Down the road, the research UNC is doing could provide an answer to what Mihalik calls a “fierce” debate concerning whether or not to add helmets to the women’s game.

As lacrosse players have gotten stronger and stick sizes have lengthened over time, the ball moves at higher speeds during a game, which can lead to concussions when players are struck.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“Shots are going at over 100 miles an hour now,” said Nina Walker, UNC men’s lacrosse head athletic trainer. “Twenty to 30 years ago that was unheard of.”

Walker and her staff are trained to watch players for concussion symptoms during games. If Walker tells Breschi a player needs to come out, she has full authority over the player until she judges he can return to action.

“If there’s an injury, they’re mine until I give them back to the coach,” Walker said.

Walker says she typically will treat anywhere from two to four players per season for concussions. She suspects the number might be higher because athletes tend to underreport symptoms of concussions but adds that it’s not as much an issue in lacrosse.

“I think that culturally, they worry a little more about their future,” Walker said. “You’re not getting a million dollar contract when you graduate, it’s more important to graduate and get a good job.”

The ultimate goal of concussion research is to make sports like lacrosse safer. But researchers say the inconvenient truth is that concussions are unavoidable in a contact sport.

Because the brain floats in fluid inside the head, any rapid acceleration or deceleration will cause the brain to smash into the skull walls like passengers in a car hitting an air bag. No amount of equipment can prevent that.

The goal, instead, is to identify dangerous situations where concussions are more likely to occur and find solutions to minimize or eliminate them.

“That’s the whole point of this,” Mihalik said. “Not to keep hoarding injury data but to understand it and to use the data to inform a very evidence-based, scientifically driven change.

“That’s the impact they’re looking to create.

sports@dailytarheel.com