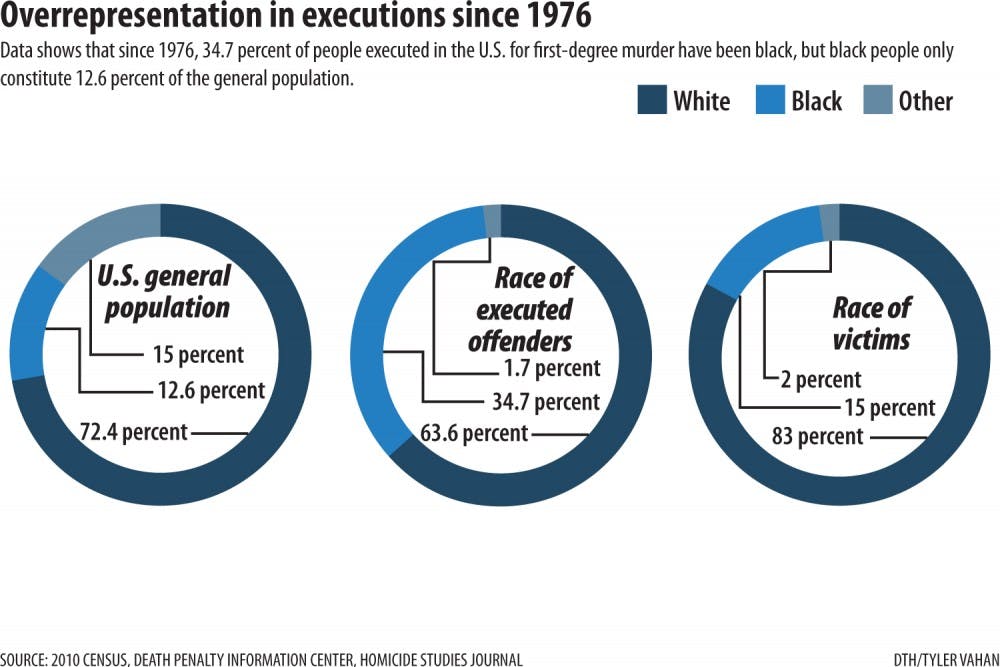

Frank Baumgartner, a UNC political science professor who specializes in capital punishment in the U.S., said if the victim in a capital case is white, it’s dramatically more likely to lead to execution.

He said on the rare occasion white killers are given the death penalty for killing people of color, it’s often in cases of blatant racism or extremism.

“When you look at those particular cases, they’re Ku Klux Klan, they’re Aryan Nations, they’re a white supremacist prison gang that kills another prisoner,” he said.

Death penalty support wavering

Kristin Collins, a spokeswoman for the Center for Death Penalty Litigation in Durham, said that while racism in capital punishment is a well-documented phenomenon, the popularity of the death penalty in general is on the decline in the U.S.

“It’s always a response that we hear to a big, high-profile crime — that we need the death

penalty,” she said.

“I actually feel like public opinion is trending away from the death penalty. A whole bunch of states have repealed it just in the past 10 years, and many other states are no longer using it, including North Carolina.”

No execution has taken place in North Carolina since 2006.

Collins said a capital conviction can hurt the families of victims by drawing out the legal process for decades, since defendants can appeal the sentence several times.

“We’ve seen some families really suffer a lot waiting decades for this execution that they think is going to make them feel better, but it never comes,” she said.

Baumgartner said only about 30 percent of capital convictions in North Carolina result in execution.

“If they go for the death penalty rather than agree on a sentence of life without the possibility of parole, Mr. Hicks will get enhanced legal protections; he’ll have more attorneys, he’ll have guaranteed appeals,” he said. “The average person on death row has already been there 15 years.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Yousef Abu-Salha, the brother of Yusor Abu-Salha and Razan Abu-Salha, said the victims’ family is focusing on returning to their normal lives in the wake of the tragedy rather than fixating on Hicks’ upcoming trial.

“It’s going to be a long and painful process, but we have faith in our justice system. Our faith and our people mean more to us than the fate of a murderer,” he said. “The hurt hasn’t gone away, but we will continue to live as proud Muslim-Americans.”

The ‘lone wolf’ narrative

Since the tragedies in Chapel Hill and in Charleston, various media outlets have tried to explain the crimes by examining the mental health and personal history of Hicks and Roof.

Both acts were immediately viewed as hate crimes, but in Hicks’ case, police and state prosecutors have said the motivation behind the Chapel Hill shooting was a long-standing parking dispute — a statement contested by the victims’ families, UNC’s Muslim Students’ Association and several other third parties.

The hesitation to label violent crimes by white perpetrators as acts of terror is a way the media criminalizes people of color while giving white people the benefit of the doubt, said Lisa Wade, an expert in race and gender in the media.

Wade said that it’s common for white killers to be treated like “lone wolves” who do not represent their race or gender, and that people of color don’t receive the same treatment.

“There’s a very strong association in American culture between black people and criminal activity. If there’s an assumption that members of a less dominant racial group are ‘up to no good’ anyway, we see violent crime as one of the normal things that happen to people who are ‘up to no good,’” she said.

“Because we elevate whiteness and we define a white person as the upstanding citizen, when a white person commits a violent crime, our global view is challenged.”

Wade said because whiteness and maleness are dominant traits in American society, they become invisible in the context of crime.

“We’re looking at this epidemic of white men doing these crimes, and yet whiteness and maleness and their intersection is not part of the media’s discussion. Nobody is asking, ‘What’s wrong with the white guy?’ even though it’s a very clear pattern.”

@Zschave

city@dailytarheel.com