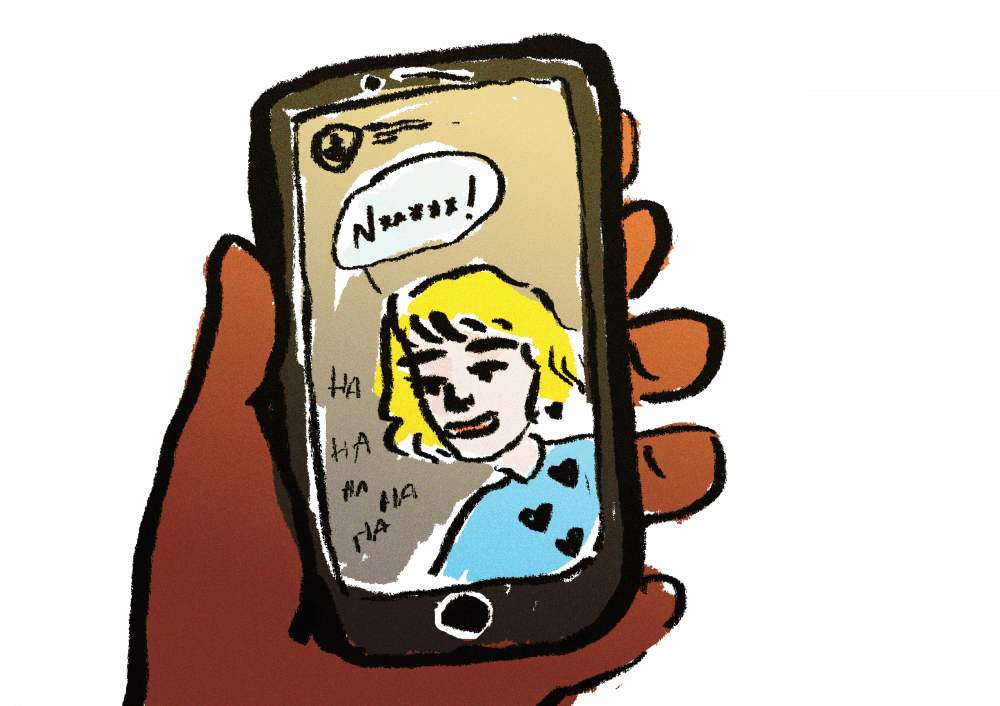

Many of us recently saw a viral video of a white person (and a UNC field hockey commit) shamelessly using the N-word, with a disturbing amount of ease and comfort, on social media.

Without proper education on the topic it can be difficult, though inexcusable, for white people to understand just how deeply offensive the N-word is. That said, in 2018: the age of the internet and public education, ignorance of the word’s history looks a lot like selective ignorance.

There is no equivalent word that can be levied against a white person, and the N-word has been accepted as offensive for so long that many who are not harmed by its extremely derogatory power have chosen to neglect its history.

With its often overlooked background and prevalence in popular music produced by (ideally) Black artists, the N-word has become subject to the same appropriation which has marked the cultural assimilation of rap and hip-hop music into the mainstream.

To some non-Black defenders of the word, the N-word has become just another bad word, another way to break norms and be subversive, no different from the F-word, S-word or B-word. Out of context, the word may be appealing for a white person trying to appear edgy or fit in with a demographic outside of their own.

But it isn’t the random grouping of letters that gives words their power, it is the idea behind them. And the idea behind the N-word has long been one of white supremacy.

Clifton Johnson, a Northern journalist writing in the early 1900s, described the use of the N-word in the South as an explicit attempt by Southerners to keep the African-American in “his place.” They used it, Johnson wrote, over terms like “colored,” “Negro,” or “black” because the N-word in particular was “recognized as opprobrious.”

Johnson even describes a scene of an old white woman reprimanding her granddaughter for using “colored” over the N-word. “Colored” was too polite, and ascribed African-Americans too much humanity for her taste.

The concepts of vernacular and connotational speech are fundamental to this debate. Typically vernacular covers geographic regions, but in the American experience, it can be applied to different groups of people. The N-word’s meaning changes based on the group of people using it. The word, in white vernacular, was and remains derogatory to keep African-Americans “in their place.” That is the connotation the word takes when spoken by a white person, full stop.