A job for a year

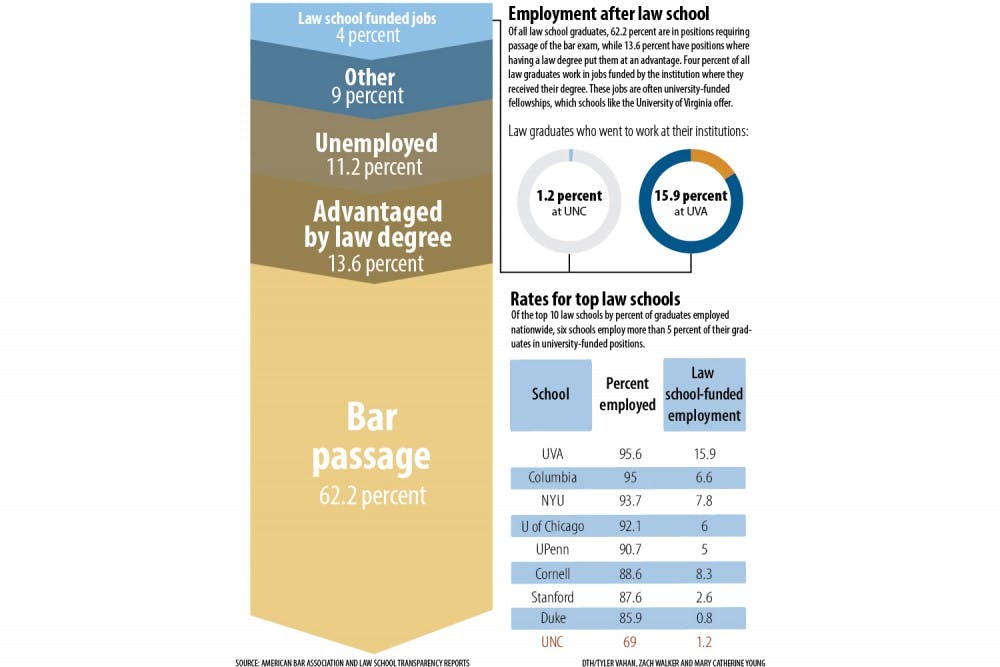

U.S. News and World Report factors in a law school’s employment rate into its rankings, as well as the type of jobs graduates hold, whether the job requires passage of the bar exam and the duration of a job.

Law schools must disclose which jobs are school-funded — a 2011 policy change — in the data they submit to the American Bar Association.

Schools must also distinguish between short-term and long-term employment. The American Bar Association considers any job that is at least one year in length to be long term. This definition accounts for federal clerkship positions, which are considered prestigious and often last one year. But many law school fellowship programs are also exactly one year.

“It does help employment statistics,” said Kyle McEntee, executive director of an advocacy organization called Law School Transparency. “But these administrators and law professors do really care about their students.”

UVa. Law School Dean Paul Mahoney said while the school does employ a number of graduates in university-funded jobs, most are participating in a yearlong fellowship program for graduates, who work in the nonprofit or government sector.

“They are not working here at the law school,” he said.

In contrast, Duke University has an employment rate of 85.9 percent, with less than 1 percent of students working in jobs funded by the school.

Duke Law’s “Bridge to Practice” program offers fellowships that are primarily short term. Stella Boswell, director of the school’s Office of Public Interest Advising, said they don’t want to offer a program that discourages their graduates from searching for a permanent job.

“We only have a handful of people who by the nine-month reporting date didn’t have other employment,” she said.

More transparent

McEntee said the data that schools release has become more transparent since 2011. Three years ago, schools only had to provide a basic employment rate to the ABA.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“You could have been a part-time barista at Starbucks, and it counted the same as a lawyer at a large firm,” McEntee said.

With the disclosure mandate, schools are required to provide a detailed breakdown of the type of employment their graduates hold to the ABA.

For some schools, the shift revealed the stark realities of the law graduate job market — at Thomas Jefferson Law School, a private institution in California, just 27 percent of graduates in the class of 2011 obtained a job that required passing the bar exam. For the class of 2010, when the school didn’t distinguish employment types, the rate was 68 percent.

UNC’s employment rate for the class of 2010 was 85 percent for all jobs, but for the class of 2011, 68 percent held a job requiring bar passage.

Some schools, like UNC, are now releasing data they are not required to disclose. The latest trend in the transparency movement is for law schools to voluntarily publish the reports that the National Association for Law Placement sends to each school. These annual reports include data on salaries and regions of employment.

UNC Law School has released each report since 2010. No school published their NALP report before 2010.

Homesley said he looked closely at schools’ employment data to see exactly where students were getting jobs.

“That’s something that really attracted me to Carolina,” he said. “There’s so much diversity in what students end up doing.”

Professor Paul Campos of the University of Colorado Law School has long advocated for greater transparency. He wrote an editorial for The New Republic in 2011 criticizing the practice of schools releasing one rate, “trumpeting employment figures of 95 percent, 97 percent and even 99.8 percent.”

In a recent interview with The Daily Tar Heel, he said law schools’ openness on employment numbers has come a long way, but still has room for improvement.

“A snapshot of what’s up with people nine months after graduation is useful,” said Campos. “But it would be much more useful to know what’s happening three and five years after graduation.

“It would be really good to know what percentage of the graduates who are in these kinds of (fellowship) programs end up getting some kind of real legal job as a result of the program.”

Campos said there is no question law schools are admitting more students than they can find jobs for.

But Lewis, of UNC law, said that employment prospects for graduates are getting better.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that it’s improving,” Lewis said. “Our students do pretty well in the job market. But it’s also true that jobs don’t grow on trees. People have to work at it.”

state@dailytarheel.com