Williamson sought care from UNC’s Student Psychological Services — which is now known as Counseling and Psychological Services — but stopped seeing a therapist the summer before the 1995 tragedy. He received referrals of where to go, but he never visited a therapist regularly again and stopped taking his medication.

His experience is one that thousands of North Carolinians seeking mental health care may have encountered — little consistency in care, lagging resources and a vast bureaucracy.

National traction for reform

Public mental health care reform gained traction nationally in the 1960s and 1970s with the nationwide move towards deinstitutionalization — an effort to move the mental health system away from state hospitals to community-based programs, said Joseph Morrissey, a UNC professor in psychiatry and health and policy management.

The mental health care system was broken up into three components: state-run hospitals, state-operated services, known as area programs, which were community programs designed to help patients on a local level, and services administered by private and nonprofit providers.

For a while, this system worked.

The area programs managed all the money allotted through state and local dollars as well as Medicaid, and they also treated patients. But serious issues with the system soon became evident, said N.C. Rep. Verla Insko, D-Orange.

Because area programs received and evaluated patients, then essentially billed themselves for the services provided, they were considered to be a conflict of interest, Insko said.

In order to counteract these financial issues, as well as increasing numbers of institutionalized patients in state-run hospitals, North Carolina legislators began the process of figuring out a way to reorganize the system. In 2001, the legislature passed a bill sponsored by Insko aimed at addressing some of the main issues.

As a result of the law, the system became privatized, with community programs contracting out to private providers for services, said Robin Huffman, executive director of the North Carolina Psychiatric Association.

Fourteen years after the bill was passed, its goals have yet to be uniformly realized across the state.

Deinstitutionalization failures

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

After the 2001 reform, the area programs were reorganized into Local Management Entities. These were local, community stations where people seeking aid for mental illness could go to find information and referrals to local providers.

The state gradually closed down Dorothea Dix, the largest state-run psychiatric hospital. Patients who were mentally ill enough to require long-term internment, such as Williamson, were moved to one of three much smaller psychiatric hospitals, reducing the number of available beds for patients.

Central Regional Hospital is one of three psychiatric hospitals in North Carolina — the other two are located in Cherry and Broughton. The 398-room hospital employs more than 1,600 staff members in a town of 7,700 residents.

Morrissey said the fragmentation in community services has caused many people to feel the reduction of the number of patient beds has gone too far.

“Community programs were never grown to the extent that was envisioned, and that has been the kind of failure, if you will, of deinstitutionalization,” Morrissey said.

As part of the reform, Insko said control of the Medicaid money was taken away from the community programs, affecting the quality and stability of care.

And because of the contracting-out system, there is no set place for people to go if they are seeking help, Huffman said.

“When patients are going to a different provider — they can choose a different provider to go to in the system — the hand-off of care is sacrificed a little bit there,” she said.

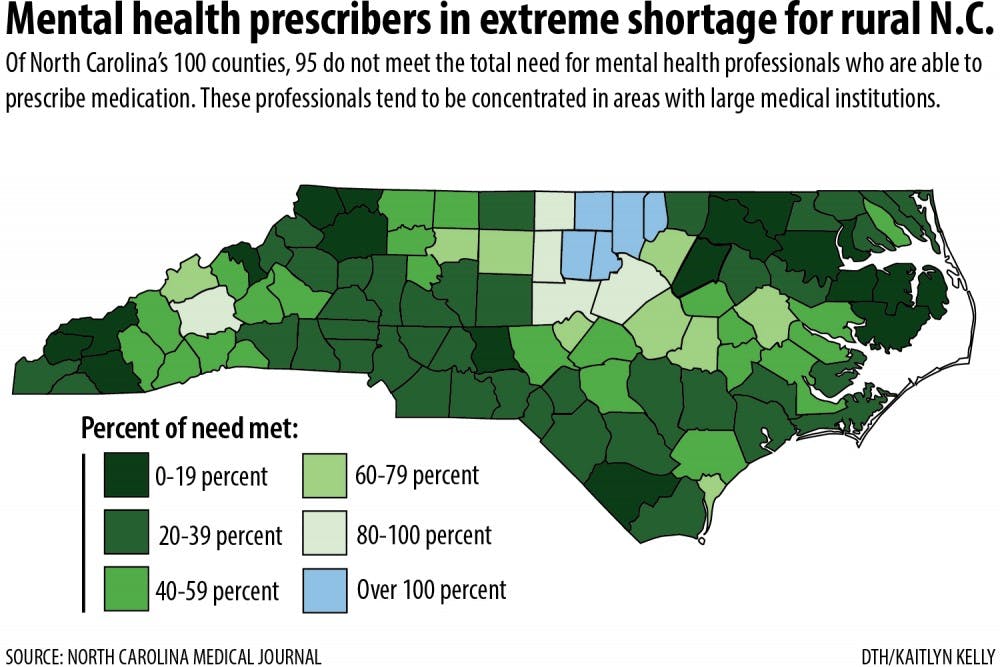

While the network of providers works to reach many of the more rural areas of the state and provide more local-based care, issues with funding and management make it more difficult to look after patients consistently.

“There’s a greater tendency for patients with more complex needs to fall between the cracks of these agencies and not to receive the services they require,” Morrissey said.

Register, of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, has worked with individuals attempting to navigate the “patchwork” of mental health care available to them for years.

“Consistency,” he said, “is the key thing. This is mental illness, this is not like an emergency room where we go in and give you a shot and send you home.”

But emergency rooms are exactly where many people suffering from psychosis end up.

According to the North Carolina Hospital Association, in 2013, North Carolina hospitals had 162,000 behavioral health emergency department visits and 68,000 inpatient behavioral health admissions.

In 2010, patients with psychological disorders accounted for almost 10 percent of all emergency room visits in North Carolina, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control, and people with mental health disorders were admitted to the hospital at twice the rate of those without.

“The emergency rooms at community hospitals have become the default safety net,” Huffman said. “People don’t know where to go.”

Instead, mentally ill patients find themselves waiting for days in emergency rooms for a space to open at a psychiatric hospital.

Moving forward

In some ways, helping close the gaps in the system is as simple as getting the word out.

“There’s a lot of stigma around behavioral health disorders and that people are hesitant to ask what they need to do,” said Dr. Keith McCoy, associate medical director and clinical advisory committee member for Cardinal Innovations Healthcare Solutions, a managed care organization in the state.

Even people who are uninsured can have access to medical health care, but McCoy said people don’t always realize this.

Since the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2012, the number of insured people in country has increased. But there are people in state who do not qualify for health care because they were intended to be covered by Medicaid.

Gov. Pat McCrory opted not to expand Medicaid in 2013 — meaning thousands of additional North Carolina residents can’t qualify for the program. McCrory has expressed hesitation about the decision, though legislative leaders remain outwardly opposed, said Rob Schofield, director of research and policy development for N.C. Policy Watch.

Morrissey said other states have used Medicaid to grow their community-based services, meaning this could give people more access to mental health care.

“Whenever you expand insurance coverage, it’s important to note that that improves the financial viability of the providers as well as services,” said McCoy. “When they’re stable, they’re able to retain better quality staff.”

And in providing consistent care to patients, quality of care is vital.

The Department of Health and Human Services is developing crisis centers as an alternative to emergency room admittance for mental health disorders. The goal of crisis centers, Insko said, is to give patients a place to stay for a few days while they are medicated and treated and able to return to their lives without needing to be institutionalized.

Huffman said in some ways returning to the mindset of team-based care that existed before the reforms could be a way of stabilizing the system.

“In our current environment, there seems to be some sense of any mental health professional can replace the other mental health professional, and that’s just not true,” she said.

Register said it’s time to stop pointing fingers.

“We need to stop reforming the reform of the reform,” he said. “Let’s let the system settle for a bit and get consistent funding.”

At the roots, it goes back to the ideas that experts say failed Williamson and the community he devastated 20 years ago: consistency of care, personal responsibility, contextualized responses — remembering and realizing that each person’s experience with mental illness is different and that society shares a collective, non-partisan goal of helping the mentally ill.

“We tend not to understand that the return on investment is a healthy person, it’s not a profit,” said Insko. “Human beings are still our best natural resource.”

special.projects@dailytarheel.com

CORRECTION: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this story misstated the name of the Cardinal Innovations Healthcare Solutions company and did not properly classify it as a managed care organization. The story also failed to clarify Keith McCoy's full title. He is the associate medical director of Cardinal Innovations Healthcare Solutions. The story has been updated to reflect these changes. The Daily Tar Heel apologizes for the errors.