“The fact that people move here is because the cost of living is great, the weather is nice and we have a lot of natural amenities — from the mountains to the coast,” Tippett said.

She said growth in metropolitan areas like Charlotte and Raleigh are driving much of the state’s overall population increase and serve as the twin engines of economic growth.

“They’re actually projected to be two of the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the country in the next 20 years,” she said.

The Rural Decline

Jason Gray, senior fellow at the North Carolina Rural Center, said rural areas of North Carolina have comparatively high population densities — they are second only to Texas.

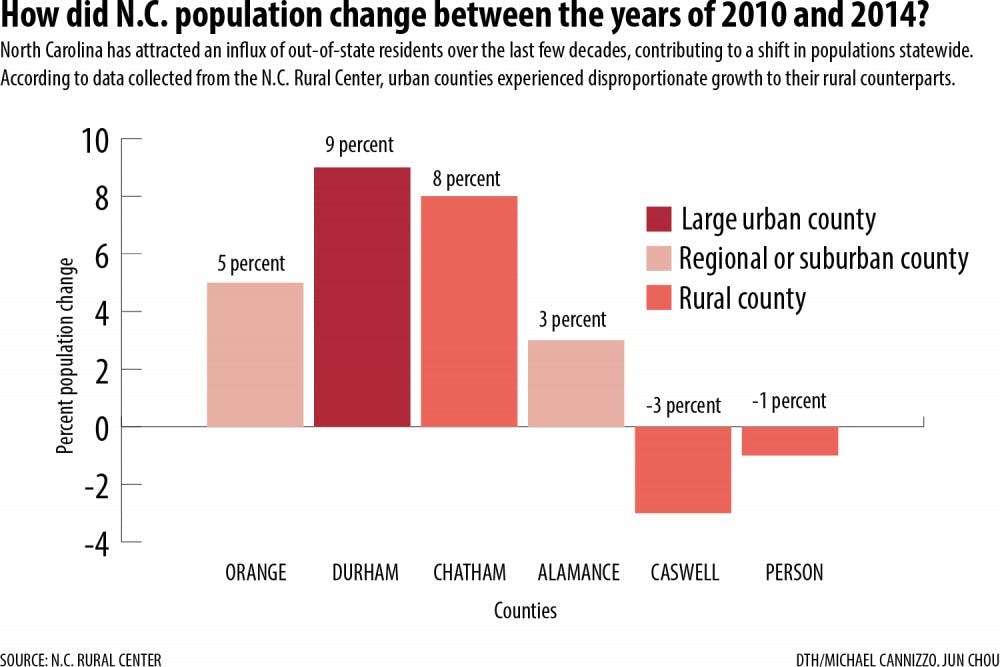

But as urban areas attract more people, rural North Carolina has suffered.

Gray said rural areas have been historically based in manufacturing, and the recent recession and loss of approximately 150,000 rural manufacturing jobs impacted the population in these areas.

The statewide loss of 310,000 manufacturing jobs caused $12.7 billion in lost income — half of which was in rural areas, he said. Even North Carolina’s advanced policies on economic development couldn’t handle that loss.

“None of that can hold up against the tidal wave of the structural change in the economy because of the shift in manufacturing,” Gray said, noting while many jobs went overseas, more were lost to technology.

Mitch Kokai, senior political analyst for the right-leaning John Locke Foundation, said the solution lies in rural counties making themselves more attractive to private investment by lowering tax burdens, decreasing regulation and increasing access to education.

“To the extent that these are available in rural North Carolina, that’s going to make it attractive to private investment, and that attraction to investments is going to be what helps drive jobs into those areas,” he said.

But Francis De Luca, president of the Civitas Institute, said improving education and the quality of life in rural areas is difficult.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“One of the problems rural counties have is that they don’t have a lot of tax revenue, and so they can’t do a lot of the things they need to do to be attractive to people,” De Luca said. “ It’s kind of a chicken-egg thing.”

Recent economic conversations have focused on recruiting out-of-state businesses, instead of supporting existing businesses, Gray said.

“I think the message that many rural communities are getting is that the state really isn’t going to make those investments,” he said. “Overall, the budget did make some changes, but it’s nowhere near what’s needed to turn the corner.”

Plowing forward

But Gray said there’s still hope, as permanent population decline is unlikely.

“I think it goes back to rural places sort of rediscovering what assets they have and building new assets that are essential for retaining young adults who live in the 21st century, not the 20th century,” he said.

He said rural communities are a great place for recent college graduates to start their own businesses because they’re more affordable than urban areas.

And according to the UNC Carolina Population Center, more college graduates move to North Carolina than leave — suggested by the 36 percent of non-native residents 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Only 19 percent of native North Carolinians boast the same level of education.

Jim Johnson, a professor in the business school at UNC, predicts college graduates will go wherever they can find jobs.

“They may end up back in North Carolina, and we would want that, but I think the nature of globalization today is you have to vote with your feet and go where the opportunity is,” he said.

He said North Carolina has become a magnet state, and he thinks it will see a lot of its population leave and then return later.

“I think we all end up making our way back home,” Johnson said.

Shannon Grand, a UNC sophomore from Atlanta, said her parents bought a farm and moved to North Carolina this year, largely because she and her sister are attending universities in the Triangle area.

She said her parents moved to Atlanta before she was born for the good school systems and because farming was too expensive, but they always wanted to live on a farm.

But Grand said she will probably live in a city after she graduates.

“The farm life is not for me,” she said. “I’ve had to help out around the farm some and it’s something I can do just occasionally when I’m visiting, but I would not like to actually live on a farm.”

Edmonds said compared to the quiet lifestyle of his hometown, living in Chapel Hill has offered new perspectives — but the farm will always be his home.

“There’s this idea in geography that there’s a difference in space and place, and so many memories and different things I’ve learned on the farm have made me have a physical connection to that place and have emotional ties,” he said. “I think it would be hard to sever that tie.”

state@dailytarheel.com