When Lauren Caton began her doctoral program at UNC, she chose to live with three other people to afford rent.

Caton is a doctoral student in the Department of Maternal and Child Health at Gillings School of Global Public Health. When she began 18 months ago, her stipend was $15,700 per year.

“I had to select a situation where I would be inconvenienced by having roommates in order to reduce the cost of rent,” she said.

Effective Jan. 1, the minimum stipend for doctoral students in the UNC Graduate School increased from $17,000 to $20,000 over a nine-month service period. Service stipends often include coverage of tuition, fees and health insurance. Any income above the minimum stipend depends on the academic department.

According to a recent Graduate and Professional Student Government survey, the average rent among over 1,100 graduate student respondents was $1,260.72 per month — about ⅔ of a monthly minimum stipend check.

And median rents in Chapel Hill have increased since 2019.

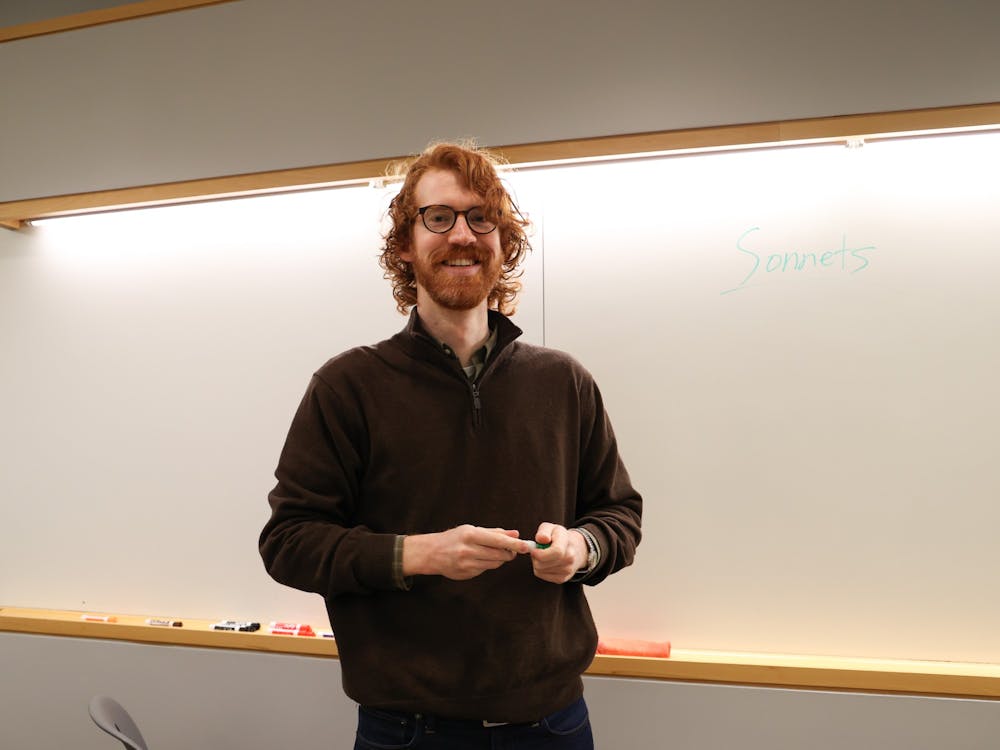

“I think one word people would use is ‘unlivable’— that Chapel Hill is an expensive place to live,” said Theodore Nollert, the president of the GPSG and a doctoral student in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. “And because of that, people either take on a bunch of roommates, they take on extra jobs or they move outside the city limits. And then they have a longer commute to campus because they’re looking for cheaper housing.”

Nearly 40 percent of graduate student respondents in the survey said they held a second job in addition to their research and teaching positions to supplement their income.

This extra money often comes from teaching extra classes at UNC or community colleges, tutoring, working service jobs or participating in freelance work.