Editor's note: In celebration of The Daily Tar Heel's 125th birthday, we are running excerpts from "Print News and Raise Hell" by Kenneth Joel Zogry. This excerpt is from pages 167-171. Books can be purchased via UNC Press.

The Dixie Classic was a basketball tournament played a few days after Christmas every year from 1949 to 1960 at Reynolds Coliseum on the campus of North Carolina State College in Raleigh. Created by legendary State head basketball coach Everett Case, the invitational tournament pitted the four leading North Carolina college teams—UNC, State, Wake Forest, and Duke—against four of the best teams from other conferences around the country. In the era before the NCAA Final Four, the Dixie Classic quickly became one of the biggest college tournaments nationally, bringing in tens of thousands of dollars (large amounts in those days), mainly to State’s athletic fund. It also quickly became a source of pride for alumni of the host schools, particularly N.C. State. But the tournament had surprising detractors as well. In a 1957 interview with the DTH, UNC head coach Frank McGuire went on record advocating the end of the Classic, referring to it as “a $60,000 slot machine,” and suggesting instead a round- robin-style tournament restricted to Atlantic Coast Conference teams. As events unfolded, McGuire’s allusion to gambling proved to be right on the money.

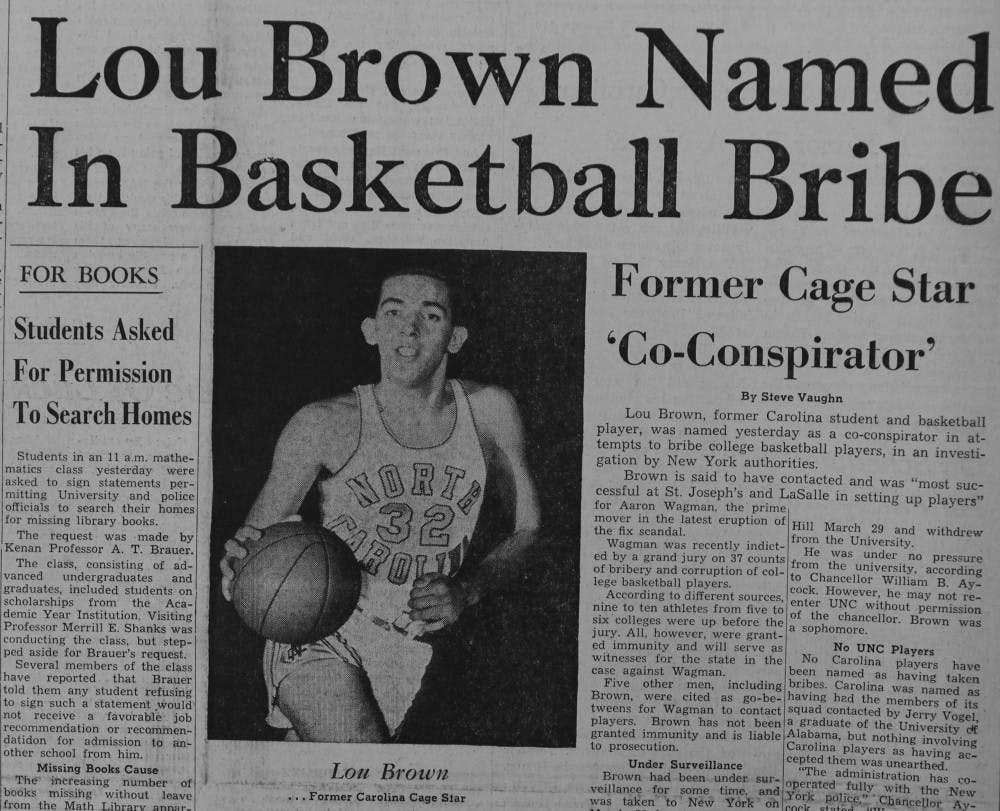

What came to be called the Dixie Classic scandal was actually the culmination of a series of events that began in September of 1960, though the incidents did not become public until the first half of 1961. In early January the Daily Tar Heel reported that an NCAA investigation into basketball recruiting irregularities at UNC had resulted in a one-year probation, which the paper supported. In February, two UNC basketball players were suspended by the ACC for fighting with Duke team members during a game. But the real trouble began in March, when details emerged about players on the Seton Hall team taking bribes to throw games. That led to a wider NCAA investigation, and the UNC community was shocked to learn in late April that a former reserve player, Lou Brown, was indicted on charges of trying to bribe current team members, bringing the burgeoning national scandal onto the Carolina campus. Apparently the previous fall Brown had approached star UNC forward Doug Moe about a scheme to “point shave,” which involved purposefully missing shots and allowing the opposing team to score, thus throwing the game or reducing the point spread. Funded by professional gamblers often attached to the criminal underworld, point shaving was a means of controlling the outcome and increasing bookie winnings on illegally placed bets. Moe accepted a “softening-up” gift of $75 to fly to New York to meet professional gambler Aaron Wagman, then thought better of it. As the scandal unfolded, it was reported that certain players on other teams had accepted up to $2,500 to throw a particular game, including two N.C. State players who threw a game with UNC in March 1961. The revelation of the involvement of professional gamblers linked to the criminal underworld marked a new low in the long history of pitfalls related to big-time intercollegiate athletics. Recently elected DTH editor Wayne King followed in the footsteps of his predecessors by condemning the evils and corruption that came with semiprofessional sports. He did not mince words about the whole rotten mess and who was to blame—not only Aaron Wagman, then widely identified by the investigation as the mastermind of the scheme, but alumni:

Some of the [players] who took bribes emerged from dirt-poor homes and rode to the crest of fame through their athletic prowess-to-be shoved back into that selfsame dirt . . . But perhaps the greatest contributors to the scandal will go unpunished. They will be the most shocked of all at the filthy affair, shaking their heads at the whole matter and dismissing it with a pious air of aloofness. Yet they have created the atmosphere on which the Wagmans capitalize . . . [An alumnus] who slips an athlete a sum of money to get him to attend a certain school—thus treating him like an animal that can be bought and sold—is as reprehensible as Wagman. Corrupting athletes was business with Wagman. . . . With the alumni it is a hobby—a hobby that is no less dangerous because it stems from school spirit.

At first the administration allowed the Men’s Honor Council, part of the school’s vaunted self- policing honor code system, to determine Doug Moe’s fate. After the council decided not to discipline Moe (as he ultimately rejected the large bribes to throw games), Chancellor William Aycock suspended him, citing information that had not been made public. In what was the first student demonstration of the 1960s at UNC, 300 students marched across campus in protest of the suspension. Aycock invited the angry students to talk with him in a hastily arranged forum in Gerrard Hall, which led to a raucous session that lasted until 2:30 in the morning, but ended with Aycock convincing most of the protesters of his position and receiving an ovation. Wayne King jumped into the fracas, first writing an editorial praising the administration for allowing the students to handle the matter, and then blasting the situation as mishandled: “It has become readily evident . . . that student government is trusted only to the extent that the administration deems sufficient.” He concluded, however, that the Moe case might have certain “good effects,” as “never, that we can remember, have students been as interested in the intricacies and problems of the Honor System.”

In early May, Lou Brown and another former basketball player, Jim Donohue, stole a penny chewing-gum machine from a hospital in Wilmington. It was unrelated to the point-shaving scandal, but now UNC varsity athletes were branded as common criminals. King responded with a powerful editorial entitled “Athletics: The Fly in the Academic Ointment.” “Everyone seems to be unwilling to admit that the whole tenor of big-time athletics is little better than rotten,” King wrote. “Athletes who are average scholastically and morally are pointed to as proof that big-time college athletics are great. But these examples are only pointed out because they are rare.” “Why,” King asked, “are coaches supposed to be good coaches only because they win, and not because they put out teams that are above reproach as men? Why does this University pour fantastic sums of money into an athletic program that is geared only to winning?” Summing up the situation, the editor concluded: “All the storm of controversy, all the slaps that this university has received because of it, will come to nothing if they do not serve to make athletics subordinate to academics and popular opinion subordinate to honest evaluation.”

As sordid as details of bribery and point shaving were—three N.C. State players were indicted for these violations in early May—the next revelation of the scandal horrified even the most ardent supporters of big-time athletics. On May 13, commencement day at UNC, President William Friday was informed that after one of the Dixie Classic games the previous December, purported mobsters appeared in the locker room and shoved guns into the stomachs of certain players who had not performed as they had been paid to do. In the wake of this stunning news, Wayne King’s words became even stronger: “It is this glorification of athletics beyond reason that is at the root of the current basketball scandals which have been so disastrously linked with the greater University. . . . The time has come for the Greater University to pull athletics down from its ill-ascended pedestal and replace it with scholarship.” Reform of the athletic program, King argued, would “require administrative courage.”

Threats against the lives of players and the involvement of the criminal underworld marked the breaking point for President Friday, who had learned invaluable lessons from the previous athletic scandals that accompanied his first year in office, and his inability to control the situation. He appeared before the consolidated university’s board and announced new procedures and imposed strict penalties—including indefinite suspension of the Dixie Classic tournament. Fallout was intense; N.C. State and UNC alumni screamed and threatened to remove the president, who successfully fought back detractors. Coaches Everett Case and Frank McGuire, however, both left their respective schools shortly after the scandal.

Friday’s rulings came a few days after the end of the spring semester and were not covered in the Daily Tar Heel; however, editorials in support of the president’s actions appeared over the ensuing two years as various efforts were made by alumni to resurrect the Dixie Classic. Certainly the policies and self-policing that Friday instituted in 1961 helped keep the worst of the athletic abuses under control at UNC for half a century. The Daily Tar Heel’s crusade against the evils of big-time sports at UNC joined a list of important causes the paper championed over the decades, from the elimination of hazing in the first decade of the twentieth century through various battles over freedom of speech at the university, to the fight for desegregation and civil rights for African Americans in the post–World War II era.