Roy Williams sits at a midweek press conference early this season in the Smith Center, answering questions about collegiate athletics.

“If we play one fewer home game, it affects field hockey, it affects baseball, it affects everything we do here,” Williams said.

Williams’ statement was in response to a potential shortening of the college basketball schedule, but his overarching point is true as well: Non-revenue sports depend on men’s basketball and football for funding.

And North Carolina’s broad-based athletics program is becoming a rarity as collegiate athletics drifts toward big money, bringing UNC along for a ride it may not be able to keep up with.

Non-revenue commitment

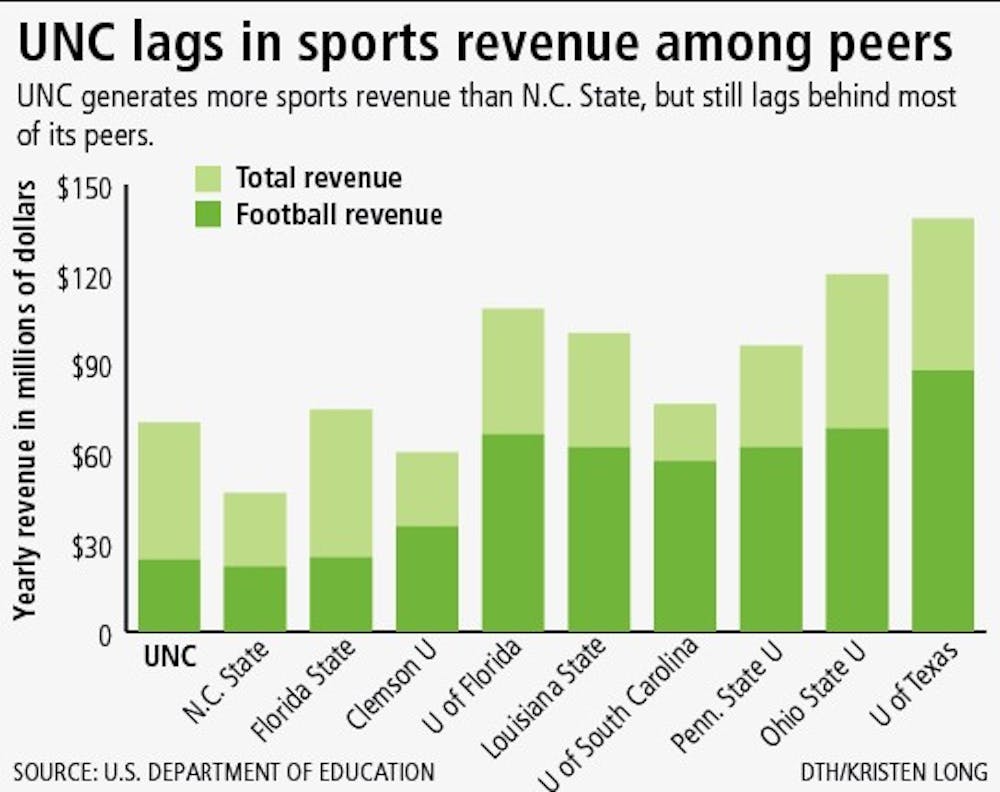

North Carolina’s athletic program contains 28 varsity programs and more than 867 varsity athletes, supported by more than $70 million of annual revenue. More than half of that revenue comes from football and men’s basketball.

In the past four years, UNC either won the NCAA title or finished as the runner-up seven times — in field hockey twice, women’s soccer three times, women’s lacrosse and men’s basketball.

Athletic Director Dick Baddour and the University are committed to supporting those non-revenue sports.

“I look at the broad-based program as a core value of the University,” Baddour said. “I believe that’s what our fans want, our students want, our faculty wants.”

But UNC and Baddour compete against a host of major universities with huge cash flows and fewer programs to support, and the Tar Heels struggle to keep pace. Many major universities opt to support the minimum 16 varsity teams required for Division-I status.

Take the University of Texas. The athletics department reported revenue of more than $138 million last year — almost double UNC’s.

But the Longhorn athletic department fields only 19 varsity teams.

“When athletic directors get together, we talk about this model,” Baddour said. “We have the same concerns. It’s like OK, does this thing blow up on us? It’s my job to see that it doesn’t.”

The stories are similar at schools in powerful football conferences like the Big 12 and SEC. Florida easily supports 16 varsity teams on its $108 million in revenue for 2008-2009.

Those schools can not only outspend UNC in football, but also in basketball, women’s soccer, gymnastics and everything else. It puts UNC sports at a competitive disadvantage across the board.

Big-money universities also report sizeable surpluses in the athletic department. Texas reported $25 million more revenue than expenses in 2008-09. Both LSU and Florida topped $6 million in surplus.

On the other hand, UNC finished 2008-09 year reporting less than $200,000 in surplus.

Making ends meet

That small and tenuous surplus is the reason that UNC pumps money into building up the football program.

Success on the field can jump-start increased revenue from football and help cushion the athletic department budget.

But UNC remains just middle-class in wins and losses despite massive investments in enclosing Kenan Stadium with premium luxury seating.

And while UNC isn’t currently close to cutting any programs, UNC’s broad-based model is under strain to fund all 28 programs.

“Sometimes when we’re putting the budget together, I’m wondering where’s that extra $25,000, $100,000 going to come from,” Baddour said.

For the non-revenue sports, that manifests itself in second-rate facilities and budget crunches. Non-revenue sports routinely go over budget, both at UNC and elsewhere in the ACC.

Coaches fill the holes with money from off-season camps, money that they could keep, based on their contracts.

“The myth is that UNC has a lot of money,” women’s lacrosse coach Jenny Levy said.

Fetzer Field, home to lacrosse, soccer, and track and field programs, is in dire need of renovations. Carmichael Arena offers a shiny new home for women’s basketball as well as extensive office space, but it’s harder to get donors to give to operating budgets.

What suffers is team travel, recruiting and daily operations — tough choices that big-money programs don’t have to make.

A ‘zero-sum game’

The Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics has already done some probing on the subject. In October, it released a survey of 119 university presidents. Many felt that the current model is unsustainable.

Hodding Carter III is a former president of the Knight Foundation, a member of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate athletics and a professor at UNC.

Carter and the commission are concerned by what he says is a “zero-sum game” in college athletics.

“Today’s expansion is just a predicate for the next one,” Carter said.

“I just think it’s a dog’s game to be constantly pursuing your own tail in this steady buildup.”

Some UNC coaches say that the solution might be to take college football out of the equation for compliance rules. Carter said that one option might be to make big-time football a semiprofessional sport. Baddour said he just wants to run a program that operates in the black.

But even Baddour agrees that changes could be in the works, saying that continuing along the trend toward big-time sports might not be infinitely sustainable.

“If we have the growth (across the board) in the next four or five years that we’ve had in the last four or five, it might not be,” he said.

Contact the Sports Editor at sports@unc.edu.

UNC athletic department struggles to make profit

UNC lags in sports revenue among peers