The recent report expands the scope of the original study to eight UNC System institutions and assesses similar concerns about freedom of expression — namely, if students are concerned about sharing their genuine political opinions in class and on campus more broadly, and why.

“I've never felt any sort of barring on what I could say or contribute to class discussions because of any sort of restrictive environment,” said Cho Nikoi, a senior history major and a fellow at the Program for Public Discourse. “But I also understand that that may be because professors are very adept at how they cultivate the classroom environment.”

In the survey, a class was randomly selected from participants’ schedules for them to consider when answering the questions. The only responses included in the report’s breakdown of student concerns were ones where the participant reported that politics came up indirectly in the course.

This subset of classes represented just under two-thirds of responses received across all eight System schools surveyed, according to the report.

This figure was misreported on the original version of the report and on the researchers’ presentations to the BOG and UNC-CH BOT. It initially stated that 36 percent of classes indirectly referenced politics. The actual figure is 64 percent of classes, Ryan confirmed in an email Sunday.

The correction of the document on Aug. 21 resulted in significantly larger differences in free expression concerns between self-identified liberal and conservative students.

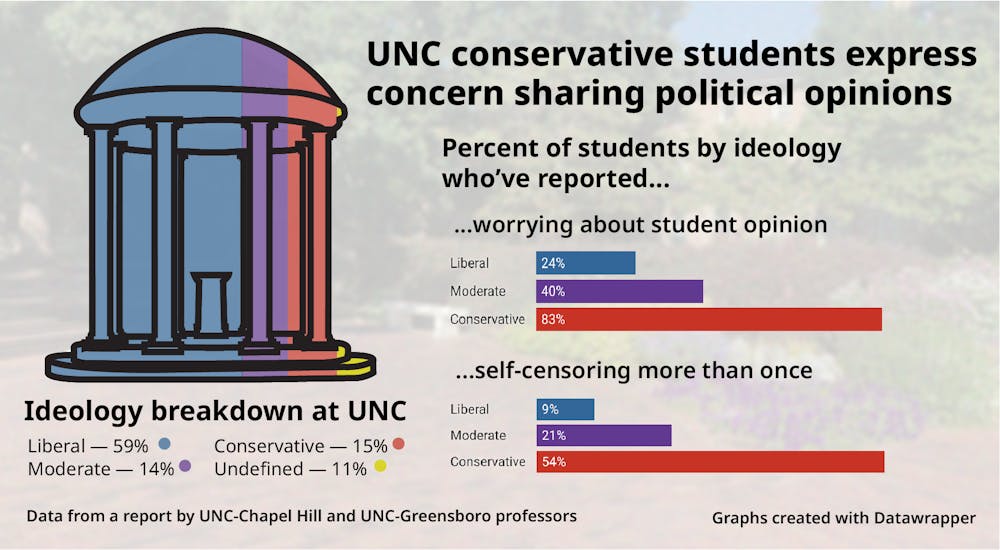

In the updated report, over half of the conservative students at UNC-CH reported self-censoring more than once in classes where politics came up, compared with less than 10 percent of liberal students.

More than 80 percent of UNC-CH's conservative students expressed concerns that their fellow students would have a lower opinion of them after they shared their genuine thoughts, compared to less than one-fourth of liberal students.

And the percentage of conservative students at UNC-CH concerned about the effect of sharing their opinions on their grades was almost seven times higher than that of liberal students.

It is worth noting that liberal students significantly outnumber conservative students at most college campuses, including those across the UNC System. According to the report, liberal students outnumber conservative students around four to one at UNC-CH.

“It sort of creates this bubble that you assume everyone has the same opinion,” McNeilly said.

This could be a contributing factor to the stark differences in self-censorship and overall concerns among students, he said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“The assumption is that everyone has a specific worldview, right?” he added. “And then when you explain you don't share that same view, there is a bit of surprise.”

Free Expression and Campus Culture

Common topics for self-censorship included race, sexuality, gender, religion and COVID-19, among other subjects. This was based on both a free response question about a specific time students self-censored and a selection question asking which topics students would feel comfortable giving their honest opinions on.

Based on open-ended response data provided by the researchers, students expressed a variety of reasons for their political self-censorship, ranging from not wanting to be perceived as racist to not wanting to get into an argument when their views were different from most classmates or professors.

Some students, particularly those identifying as Black, Indigenous and people of color or LGBTQ+, said they were concerned about their safety and emotional labor in relation to their identity.

Overall, in-class concerns about sharing political opinions mostly focused on student impressions. Thirty-five percent of UNC-CH student responses involved worries about what their fellow students would think about them, compared to 24 percent that included concerns about their professor’s opinion of them and 15 percent that reported concerns about an impact on their grade.

According to the report, these numbers are significantly higher for conservative students compared to liberal or moderate students.

The report’s conclusion notes the consideration that there may be a reason for the censored opinions being held back.

“Perhaps the views being held back do not have a legitimate role to play in civil discourse,” the report states. “Perhaps they are mean-spirited. Perhaps the consequences that students expect to come from expressing them should be conceptualized not as closed-mindedness, but as an effort to protect one’s self or one’s peers from bigotry or hate.”

Ryan said this caveat was added to the report after concerns from primarily liberal readers of the 2020 report.

“I don't think that's true of our students, by and large,” he said. “But we were going to do the best job we can to kind of figure out what it is that they're holding back.”

When it comes to addressing some of the concerns that the report highlighted, McNeilly said that training people more effectively to engage with difficult conversations and differing opinions would help resolve the problem of self-censorship.

On the classroom level, a lot of that is dependent on instructors facilitating a classroom and community environment that focuses on engaging and protecting students — and building trust, said Tori Ekstrand, a professor that teaches media law courses at the Hussman School of Media and Journalism.

“I spent a lot of time on that — a number of my colleagues do the same thing,” Ekstrand said. “If people are going to talk to each other, there has to be a level of trust that's established, and that doesn't happen just by handing out a syllabus.”

@hannahgracerose

university@dailytarheel.com