Brent Bailey was in prison from March 1999 to April 2004, convicted of conspiring to traffic cocaine when he was 23 years old. He said his addiction to weed and acid began when he was around 18 years old, and his drug usage led to drug selling.

He kept his mind on his wife and son during his time in prison and eventually was able to be part of a work-release program.

Bailey said he feels that he was in a better position to succeed after leaving prison, not only because of the support of Project Re-entry, a transition program to help prepare for life after prison, but also because he was able to return home to his family.

But he said these advantages didn’t make it any less difficult to find to find a job.

The manufacturing job making furniture that he had held for 18 months while participating in the work-release program was shipped overseas three months before his sentence ended. The good job he’d expected to have was gone.

His first job after prison was at Bojangles'.

He didn’t want to work at Bojangles'.

“But, what you gonna do?” Bailey said. “You gonna get back in the streets, risk your freedom and go back to prison? Or you gonna start where you have to and climb from there?”

He took the job but kept searching for work. After three weeks, Bailey found a job at Highland Industries that paid double what he earned at Bojangles’.

Six years later, Bailey saw a job advertisement posted on Goodwill's website, looking for a prison re-entry specialist. He hadn’t realized that he was applying for a job in Project Re-entry. He was the first person the program had hired that had completed the program.

Bailey has been a program coordinator for almost 11 years. And through this program, he began telling his story across the state and finding fulfillment helping others.

Bailey had begun to get more involved in advocacy through his work, and after meeting Daryl Atkinson, co-director of Forward Justice, he became part of the Second Chance Alliance. Bailey is now a program coordinator for the alliance in Buncombe County.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“Some people really did just make a horrible decision at a horrible time,” Bailey said at a Goodwill event in 2018. “All they need is an opportunity to show their worth and value.”

“Maybe their life can get better”

When she was unable to earn enough money to provide for her children in the 1980s, Burke was convinced by her kids’ father to cash the stolen checks he gave her. The first time she got caught, she was put in jail for six months. The second time, it was 20 months.

After being released, Burke immediately found herself struggling to provide again because her criminal record made it difficult to find and keep a job.

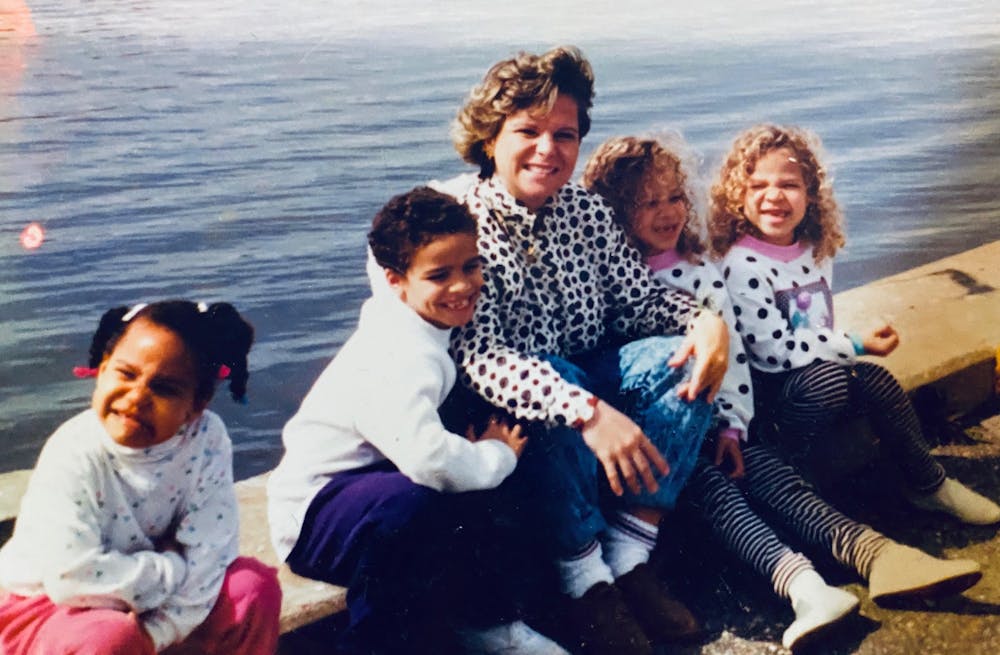

She solved this by starting her own flower delivery service called “Petal Pushers,” which allowed her to raise her four kids.

When her youngest daughter graduated high school, Burke felt inspired to return to school. While at N.C. State University, a civics class she took motivated her to consider law school.

“I thought to myself, well, that would be something,” Burke remembers. “If you learn that, then you could probably help a lot of people.”

Burke graduated from N.C. Central University School of Law in 2010.

She was now a lawyer, licensed in Washington, D.C. — but not the state she lives in because of her record. Burke began talking with friends about how she believed expungement laws in North Carolina were lacking.

These conversations led her to Daniel Bowes, who worked with the N.C. Justice Center, and other ex-offenders who similarly struggled with their records. Together, they helped build a coalition that would become the Second Chance Alliance.

“In 2011, we began walking around with our little signs, so people can have hope and they know that maybe their life can get better,” Burke said about the start of their movement, when only a handful of demonstrators joined them.

Burke remembers what it is like to not have hope. She knows that without it, people may just give up. She said when people think their life can’t get better, they stop trying, which makes them more at risk of getting in trouble again.

She said she believes the Second Chance Act gives hope back to people who need it.

On May 7, 2019, over 1,000 people joined with the alliance for the Second Chance Lobby Day in front of the legislature building to pressure them to pass the act.

On June 25, 2020, Bailey and Burke took a moment to celebrate the act being signed into law before getting back to work. There is more they can do for criminal justice reform, and an election is coming up.

“We didn’t get everything we want, but they cracked the door open,” Bailey said. “Now we got our foot in there, and every year, we’re coming back.”

@DTHCityState | city@dailytarheel.com

@brittmcgee21