The Lumbee Tribe, the largest Indigenous tribe in North Carolina and east of the Mississippi River, is continuing its 135-year-long pursuit of federal recognition through the Lumbee Fairness Act.

The Lumbee Fairness Act was introduced by Sens. Ted Budd (R-N.C.) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) in the Senate on February 17. This piece of legislation is one of many attempts at federal recognition for the Lumbee in past years.

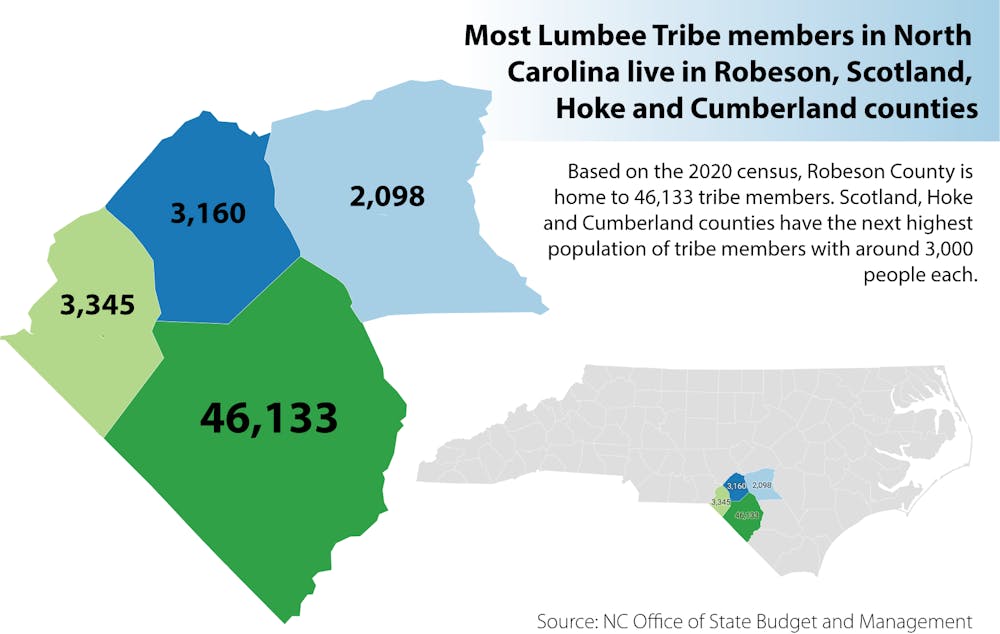

The Lumbee, whose tribal territory is located in southeastern North Carolina in Robeson, Hoke, Cumberland and Scotland counties, became one of North Carolina’s eight state-recognized Indigenous tribes in 1885.

Three years after gaining state recognition, the Lumbee began pursuing full federal recognition. In 1956, Congress passed the Lumbee Act, which acknowledged the Lumbee as a tribal nation, but denied the Lumbee services and benefits from the government.

“We are continuing to ask Congress to get right what their predecessors got wrong,” John Lowery, the chairperson of the Lumbee Tribe, said.

Though the Lumbee Tribe — which has more than 55,000 members — does not receive the financial resources from the government that other federally recognized tribes do, the tribe works to provide housing, health and education services to members.

“I want people to know that we are a tribal entity, we are a tribal government, we are a government that is self-sustaining,” Lowery said.

Lowery believes that if the Tribe can gain federal recognition status, these resources will increase economic development in the tribal territory, he said.

If the tribe was federally recognized, it would have access to funds and programs run by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs and would have access to health care through Indian Health Service.